Adrenochrome

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

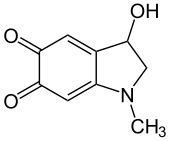

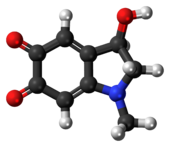

| IUPAC name

3-Hydroxy-1-methyl-2,3-dihydro-1H-indole-5,6-dione

| |

| Other names

Adraxone; Pink adrenaline

| |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.176 |

| EC Number |

|

PubChem CID

|

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| Properties | |

| C9H9NO3 | |

| Molar mass | 179.175 g·mol−1 |

| Appearance | deep-violet[1] |

| Density | 3.785 g/cm3 |

| Boiling point | 115–120 °C (239–248 °F; 388–393 K) (decomposes) |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

Adrenochrome is a chemical compound produced by the oxidation of adrenaline (epinephrine). It was the subject of limited research from the 1950s through to the 1970s as a potential cause of schizophrenia. While it has no current medical application, the semicarbazide derivative, carbazochrome, is a hemostatic medication.

Despite this compound's name, it is unrelated to the element chromium; instead, the ‑chrome suffix indicates a relationship to color, as pure adrenochrome has a deep violet coloration.[1]

Chemistry

The oxidation reaction that converts adrenaline into adrenochrome occurs both in vivo and in vitro. Silver oxide (Ag2O) was among the first reagents employed for this,[2] but a variety of other oxidising agents have been used successfully.[3] In solution, adrenochrome is pink and further oxidation of the compound causes it to polymerize into brown or black melanin compounds.[4]

History

Several small-scale studies (involving 15 or fewer test subjects) conducted in the 1950s and 1960s reported that adrenochrome triggered psychotic reactions such as thought disorder and derealization.[5]

In 1954, researchers Abram Hoffer and Humphry Osmond claimed that adrenochrome is a neurotoxic, psychotomimetic substance and may play a role in schizophrenia and other mental illnesses.[6]

In what Hoffer called the "adrenochrome hypothesis",[7] he and Osmond in 1967 speculated that megadoses of vitamin C and niacin could cure schizophrenia by reducing brain adrenochrome.[8][9]

The treatment of schizophrenia with such potent anti-oxidants is highly contested. In 1973, the American Psychiatric Association reported methodological flaws in Hoffer's work on niacin as a schizophrenia treatment and referred to follow-up studies that did not confirm any benefits of the treatment.[10] Multiple additional studies in the United States,[11] Canada,[12] and Australia[13] similarly failed to find benefits of megavitamin therapy to treat schizophrenia.

The adrenochrome theory of schizophrenia waned, despite some evidence that it may be psychotomimetic, as adrenochrome was not detectable in people with schizophrenia.[citation needed]

In the early 2000s, interest was renewed by the discovery that adrenochrome may be produced normally as an intermediate in the formation of neuromelanin.[5] This finding may be significant because adrenochrome is detoxified at least partially by glutathione-S-transferase. Some studies have found genetic defects in the gene for this enzyme.[14]

Adrenochrome is also believed to have cardiotoxic properties.[15][16]

In popular culture

- In his 1954 book The Doors of Perception, Aldous Huxley mentioned the discovery and the alleged effects of adrenochrome, which he likened to the symptoms of mescaline intoxication, although he had never consumed it.[17]

- Anthony Burgess mentions adrenochrome as "drencrom" at the beginning of his 1962 novel A Clockwork Orange. The protagonist and his friends are drinking drug-laced milk: "They had no license for selling liquor, but there was no law yet against prodding some of the new veshches which they used to put into the old moloko, so you could peet it with vellocet or synthemesc or drencrom or one or two other veshches [...]"[17]

- Hunter S. Thompson mentioned adrenochrome in his 1971 book Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas.[18] This is the likely origin of current myths surrounding this compound, because a character states that "There's only one source for this stuff ... the adrenaline glands from a living human body. It's no good if you get it out of a corpse." The adrenochrome scene also appears in the novel's film adaptation.[17] In the DVD commentary, director Terry Gilliam admits that his and Thompson's portrayal is a fictional exaggeration. Gilliam insists that the drug is entirely fictional and seems unaware of the existence of a substance with the same name. Hunter S. Thompson also mentions adrenochrome in his book Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail '72. In the footnotes in chapter April, page 140, he says: "It was sometime after midnight in a ratty hotel room and my memory of the conversation is hazy, due to massive ingestion of booze, fatback, and forty cc's of adrenochrome."

- In the first episode of the ITV series Lewis, "Whom the Gods Would Destroy", the motive for the crimes was that a prostitute had been killed years previously to harvest her adrenal glands.

- Adrenochrome is mentioned in the 2014 Warhammer 40,000 novel The Talon of Horus by Aaron Dembski-Bowden. It is described as a clear liquid beverage that is, "harvested from the adrenal glands of living slaves [...]"

- Adrenochrome is a subject of several far right conspiracy theories, such as QAnon and Pizzagate,[19][20][21] with the chemical helping the theories play a similar role to earlier blood libel and Satanic ritual abuse stories.[22] The theories commonly state that a cabal of Satanists rape and murder children, and "harvest" adrenochrome from their victims' blood as a drug[23][24] or as an elixir of youth.[25] In reality, adrenochrome has been produced by organic synthesis since at least 1952,[26][27] is synthesized by biotechnology companies for research purposes, and has no medical or recreational uses.[28]

References

- ^ a b Heacock RA, Nerenberg C, Payza AN (1 May 1958). "The Chemistry of the "Aminochromes": Part I. The Preparation and Paper Chromatography of Pure Adrenochrome". Canadian Journal of Chemistry. 36 (5): 853–857. doi:10.1139/v58-124.

- ^ Veer WL (1942). "Melanin and its precursors II. On adrenochrome". Recueil des Travaux Chimiques des Pays-Bas. 61 (9): 638–646. doi:10.1002/recl.19420610904.

- ^ Heacock RA (1 April 1959). "The Chemistry Of Adrenochrome And Related Compounds" (PDF). Chemical Reviews. 59 (2): 181–237. doi:10.1021/cr50026a001.

- ^ A. Hoffer, H. Osmond (22 October 2013). The Hallucinogens. Elsevier. pp. 272–273. ISBN 978-1-4832-6169-0.

- ^ a b Smythies J (January 2002). "The adrenochrome hypothesis of schizophrenia revisited". Neurotoxicity Research. 4 (2): 147–150. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.688.3796. doi:10.1080/10298420290015827. eISSN 1476-3524. ISSN 1029-8428. OCLC 50166444. PMID 12829415. S2CID 37594882.

- ^ Hoffer A, Osmond H, Smythies J (January 1954). "Schizophrenia: A New Approach. II. Result of a Year's Research". The Journal of Mental Science. 100 (418): 29–45. doi:10.1192/bjp.100.418.29. eISSN 1472-1465. ISSN 0007-1250. LCCN 89649366. OCLC 1537306. PMID 13152519. S2CID 42531852.

- ^ Hoffer A, Osmond H (First Quarter 1999). "The Adrenochrome Hypothesis and Psychiatry". The Journal of Orthomolecular Medicine. 14 (1): 49–62. ISSN 0834-4825. OCLC 15726974. S2CID 41468628. Archived from the original on 20 February 2024. Retrieved 15 March 2024.

- ^ Hoffer A, Osmond H (1 January 1968). The Hallucinogens (First ed.). Academic Press. ISBN 978-0123518507. LCCN 66030086. OCLC 332437. OL 35255701M. Retrieved 15 March 2024 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Hoffer A (1994). "Schizophrenia: An Evolutionary Defense Against Severe Stress" (PDF). Journal of Orthomolecular Medicine. 9 (4): 205–2221.

- ^ Lipton MA, Ban TA, Kane FJ, Levine J, Mosher LR, Wittenborn R (1973). "Task Force Report on Megavitamin and Orthomolecular Therapy in Psychiatry" (PDF). American Psychiatric Association. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 February 2021. Retrieved 7 September 2020.

- ^ Wittenborn JR, Weber ES, Brown M (1973). "Niacin in the Long-Term Treatment of Schizophrenia". Archives of General Psychiatry. 28 (3): 308–315. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1973.01750330010002. PMID 4569673.

- ^ Ban TA, Lehmann HE (1970). "Nicotinic Acid in the Treatment of Schizophrenia: A Summary Report". Schizophrenia Bulletin. 1 (3): 5–7. doi:10.1093/schbul/1.3.5.

- ^ Vaughan K, McConaghy N (1999). "Megavitamin and dietary treatment in schizophrenia: a randomised, controlled trial". Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 33 (1): 84–88. doi:10.1046/j.1440-1614.1999.00527.x. PMID 10197889. S2CID 38857700.

- ^ Smythies J (2004). Smythies J (ed.). Disorders of Synaptic Plasticity and Schizophrenia (1st ed.). Elsevier Academic Press. pp. xv. ISBN 978-0-12-366860-8.

- ^ Bindoli A, Rigobello MP, Galzigna L (July 1989). "Toxicity of aminochromes". Toxicology Letters. 48 (1): 3–20. doi:10.1016/0378-4274(89)90180-X. hdl:11577/2475305. PMID 2665188.

- ^ Behonick GS, Novak MJ, Nealley EW, Baskin SI (December 2001). "Toxicology update: the cardiotoxicity of the oxidative stress metabolites of catecholamines (aminochromes)". Journal of Applied Toxicology. 21 (S1): S15 – S22. doi:10.1002/jat.793. PMID 11920915. S2CID 27865845.

- ^ a b c Adams J (7 April 2020). "The truth about adrenochrome". The Spinoff. Retrieved 28 June 2020.

- ^ Friedberg B. "The Dark Virality of a Hollywood Blood-Harvesting Conspiracy". Wired. Retrieved 21 February 2021.

- ^ "Fear and adrenochrome". Spectator USA. 4 May 2020. Archived from the original on 20 September 2020. Retrieved 23 May 2020.

- ^ "How Facebook connects 'pizzagate' conspiracy theorists". NBC News. February 2019. Retrieved 23 May 2020.

- ^ Dunning B (20 October 2020). "Skeptoid #750: How to Extract Adrenochrome from Children". Skeptoid. Retrieved 20 October 2020.

- ^ Kantrowitz L (29 September 2020). "QAnon, Blood Libel, and the Satanic Panic". The New Republic. Retrieved 8 May 2021.

- ^ Friedberg B (31 July 2020). "The Dark Virality of a Hollywood Blood-Harvesting Conspiracy". Wired. Retrieved 16 February 2022.

- ^ Hitt T (14 August 2020). "How QAnon Became Obsessed With 'Adrenochrome,' an Imaginary Drug Hollywood Is 'Harvesting' from Kids". The Daily Beast. Retrieved 27 January 2021.

- ^ "QAnon: A Glossary". Anti-Defamation League. 21 January 2021. Retrieved 15 February 2022.

- ^ Schayer, Richard W. (1952). "Synthesis of dl-Adrenalin-β-C14 and dl-Adrenochrome-β-C14". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 74 (9). ACS Publications: 2441. doi:10.1021/ja01129a531. Archived from the original on 25 October 2022. Retrieved 25 October 2022.

- ^ "Method of synthesizing adrenochrome monoaminoguanidine". Google Patents. 1965. Archived from the original on 16 October 2021. Retrieved 25 October 2022.

- ^ Walker-Journey, Jennifer (14 April 2021). "Untangling the Medical Misinformation Around Adrenochrome". HowStuffWorks. Archived from the original on 14 April 2021. Retrieved 25 October 2022.

External links

- Joe Schwarcz PhD QAnon’s Adrenochrome Quackery 10 Feb 2022 Office for Science and Society, McGill University

- Adrenochrome Commentary at erowid.org

- Adrenochrome deposits resulting from the use of epinephrine-containing eye drops used to treat glaucoma from the Iowa Eye Atlas (searched for diagnosis = adrenochrome)